While we all know what types of films the adjective “exploitation” refers to, I’ve often wondered exactly who or what is the object of the exploitation in question? Is it the audience, the film or, perhaps, a particular subject matter? These answers are not mutually exclusive, since in truth the answer is likely all three. These films exploit lurid or disturbing subject matter, often at the expense of quality. The advertising for such films does this as well, attempting to shock and/or titillate, as opposed to focusing on a film’s quality, stars or artistic aspects. And, of course, the film and its advertising are each exploiting the audience’s more prurient interests for financial gain. In this scenario, usually everyone involved is left satisfied – the filmmakers make their money and the audience gets to enjoy sating their desire to watch films their mother would probably prefer they didn’t. In terms of this arrangement, The Toolbox Murders (1978) is a complete and utter success, while its 2003 remake exploits very little other than its own title.

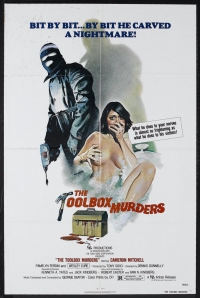

The Toolbox Murders (1978) is an excellent example of the term “exploitation film.” Its poster art features a nearly nude woman bathing in front of a masked assailant carrying a power drill. A hammer forms the second ‘T’ in the title, which sits atop a toolbox leaking blood. “Bit by bit… by bit he carved a nightmare!” the poster rather awkwardly exclaims. “What he does to your nerves is almost as frightening as what he does to his victims!” an oddly placed placard reads. This poster is attempting to communicate one singular message – “This movie has more blood and tits than you could possibly imagine, so go f’ing see it!” – a message it gets across successfully, albeit bluntly. I don’t know how well this film delivers on that promise, but in terms of its advertising, any theater patron coming across this poster knows instantly what the film is about and whether they want to see it. More than thirty years later, it is still rare to find film advertising that so clearly and succinctly communicates its message at a single glance.

Beyond the actual film and its advertising, the idea for the film was born not from creative desire, but from financial aspiration. In many ways, the story of the making of the film is more interesting than the film itself. Producer Toni DiDio noticed that The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was playing at his local theater for a second run. Amazed, he asked the distributor to send him a copy of the movie and he pulled together a television director and a writing team and invited them to a private screening of the film. They were told that when the film started, they would know what it was and their job was to come up with an idea for this film’s market. Toni, the driving force behind The Toolbox Murders, then waited next door for the film to end because he didn’t really like horror films.

We all know the film business is just that – a business, but rarely do you see it so plainly as here. The Toolbox Murders only exists because a producer saw a niche he thought was not fully exploited, and he crafted a film to fit it. Its goal was not to be a better film than Tobe Hooper’s masterpiece, but simply to be a similar film (with additional blood and nudity) that would appeal to the same audience. In those regards, the film is a resounding success and I can’t imagine audiences being disappointed. This is a film that’s title and poster scream “this is the kind of movie where you might get to see a naked woman get murdered with a nailgun.” And, about halfway into the film, that’s exactly what it delivers.

Given that The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was the inspiration for The Toolbox Murders, it’s ironic that Tobe Hooper would end up directing the latter film’s 2003 remake. You would think part of the reason Tobe was chosen was that the producers were aware of his influence on the original film, but the decision seems to be based simply on the fact that Tobe was the most well-known director they could get for the money available. Regardless, any failings of The Toolbox Murders (2003) in terms of camera work, editing, lighting or other directorial responsibilities may fall on the shoulders of Tobe Hooper, but the film’s failure as a remake of an exploitation classic fall largely with the producers.

The Toolbox Murders (1978) is not a film for everyone and, given its subject matter, its no mystery why fans of the film are in the minority. No one is under any obligation to watch the film except, one might reasonably argue, the people responsible for remaking it. And yet on the commentary track for The Toolbox Murders (2003), producers Jascqueline Quella and Terence Potter clearly state that they couldn’t watch more than a few minutes of the original film. Quella goes so far as to call it “the most misogynistic film I’d ever seen,” an opinion based on seeing only a small fraction of the entire film. When the producers obtained the rights to the film’s title, it came with a draft of a script similar to the original film, which was quickly discarded. With Tobe Hooper attached as director, they began crafting a new script, one with a much different agenda than that of the 1978 film. The original film’s plot was, as you’d probably expect, exceedingly simple. A crazed lunatic kills women in an apartment complex with various household tools in response to a past trauma. He continues killing young women in various states of undress until one of the victims fights back. In the 1980s, this premise would become the basic formula for dozens, if not hundreds, of other exploitative slasher films.

The producers of The Toolbox Murders remake, however, decided their film would go in a different direction. The basic slasher concept was replaced with a story that focuses on the mystery of how an old apartment complex came to be built. Women and men are now killed, and there is no nudity. And, perhaps strangest of all, the killer is not a deranged sexual predator and psychopath but instead a 100-year-old warlock who uses his victims and the hotel itself to cast a spell to keep himself alive for centuries.

While I doubt I am the first to say it after learning of the plot of this film, I’d like to take this moment to officially say, “What the hell?” To be fair, the killer does, in fact, kill using tools – but that has little to do with the plot or an appreciation of the original film and everything to do justifying the film’s title.

In terms of financial success, the reason for remaking a film is to bank on the popularity of the original. Rarely does a remake replicate its source material exactly (a notable exception being the blasphemous Psycho remake), but it would seem wise to make a strong attempt to a film that, by-and-large, would appeal to the same audience as the original. I have no issue with someone making a film about a male witch who lives in the walls of a Hollywood building in an attempt to achieve eternal life. However, I don’t think that’s the film anyone would expect to see when paying to watch a remake of The Toolbox Murders.

The Toolbox Murders (2003) is an exploitative film, but not really of the variety I described earlier. Instead of exploiting a certain topic, marketing niche or people’s less than noble desires, this film is simply exploiting the audience of the original film. It’s a bait-and-switch, based not on audience expectations but on the personal preferences of the film’s producers. Toni DiDio may not have been a fan of slasher films, but his job was to deliver a film that would satisfy audiences that did. Given the financial success of The Toolbox Murders (1978), it’s obvious this goal was achieved. The remake, on the other hand, is far less successful, both creatively and financially. The answer to why this may be seems obvious – the film fails to deliver on the promises that the title and claims of being a remake entail. Furthermore, fans of spooky apartment/mystical drywall-concealed witch stories can hardly be blamed for failing to recognize this film as such, based on its title.

Successful remakes are a new take on an existing story that remains true in spirit to the original. Successful exploitation films may not deliver all the thrills, chills or brassiere cup sizes that the posters may imply; but they do not leave the audience feeling as though they just wasted their money. It’s unfortunate both for fans of the original film and fans of Tobe Hooper’s work that The Toolbox Murders (2003) fails on both these counts. You would think that remaking a film like The Toolbox Murders would be a rather self-evident and simple task, but in what must have been a task comparable to salmon swimming upstream, the forces behind the remake seemed hell-bent on proving this wrong. Removing not just the basic plot but almost everything that makes exploitation films what they are, The Toolbox Murders (2003) is an empty, soulless film that takes itself far too seriously and leaves all the fun back in the decade of disco, leisure suits and pet rocks.

4 Responses to The Toolbox Murders (1978) and The Toolbox Murders (2003)

Pingback: Top 100 Slasher Horror Movies

Pingback: The Toolbox Murders (1978) | Old Old Films

Subscribe Without Commenting