I’ll admit that I love poetry every bit as much as I love horror films. In fact, I’ll argue that real poetry is less about the touchy-feely pleasures of sunshine, fields of golden barley, and lovely trees than it is a harrowing exploration and expression of the complexities of the human condition. While it’s true that most poets choose not to write explicitly about zombies and flesh-eating blobs from beyond the stars, they do sometimes use language, imagery, and metaphors surprisingly similar to horror films in order to explore the darker side of the human experience. To prove to you that poetry is not for the faint of heart, I offer the following list of poems that I think fans of horror films ought to know and love.

10. “Dulce et Decorum Est” (1917) by Wilfred Owen

|

…If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in, And watch the white eyes writhing in his face, His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin; If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs, Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,– My friend, you would not tell with such high zest To children ardent for some desperate glory, The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori. |

Wilfred Owen was only twenty-four when he wrote his most famous poem, which he based on his first-hand experiences with chemical warfare during Word War I. As evident in the closing section of the poem above, his imagery is brilliant and still shocking. Special effect artists could do a lot worse than this poem as a manual for how to make a believable zombie. In fact, when I visualize this poem, I imagine George Romero’s zombie series, but there are plenty of other monsters in this poem, including devils, witches, and madmen.” All of it points to the ugly truth that war is the ultimate act of horror and produces hordes of the living dead even as it produces heroes. It’s no coincidence that some of the best practitioners in the horror genre have either experienced war firsthand (e.g., Tom Savini) or were significantly impacted by it during their formative years (e.g., George Romero). In fact, nearly every zombie movie I can think of has at least a tangential link between zombie-hood and the politics of our modern industrial military complex. If “Dulce et Decorum Est” weren’t horrifying enough without its graphic and relentless imagery, it’s worth noting that Owen died in battle just after he wrote it, and one year before the war ended.

9. “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner” (1945) by Randall Jarrell

|

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze. Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life, I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters. When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose. |

This little five-line poem is probably the most widely anthologized piece from this countdown. As with Owen, Jarrell writes from first-hand experience. He served in the air force during Word War II, and his poems also pulse with the same visceral and haunting imagery as Owen’s. Jarrell’s imagery is particularly monstrous in its combination of initial tenderness and then sudden inhumanity. The speaker begins in simple animal existence, then transforms into little more than a state apparatus, and then reverts back again to a more grotesque form of flesh and bone. The way the speaker is so bluntly and so thoroughly reduced to either raw flesh or indifferent machine is reminiscent of Cronenburg. Films such as The Fly illustrate that technology can provide some promise of transcendence, but never beyond the confines of the physical animal in us all. “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner” likewise depicts the grisly way in which technology, especially during war, becomes a perverse nightmare when it replaces our better, more humane natures. Jarrell survived the war, but was never the same. He had a brilliant career as a writer and teacher, but he suffered from lifelong depression and died under mysterious circumstances by apparently walking into oncoming traffic in Chapel Hill, NC.

8. “Jerusalem” (1804) by William Blake

|

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England’s mountains green? And was the holy Lamb of God On England’s pleasant pastures seen? And did the Countenance Divine Shine forth upon our clouded hills? And was Jerusalem builded here Among these dark Satanic mills? Bring me my bow of burning gold: Bring me my arrows of desire: Bring me my spear: O clouds unfold! Bring me my chariot of fire. I will not cease from mental fight, Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand Till we have built Jerusalem In England’s green and pleasant land. |

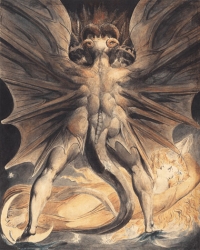

William Blake was better known in his own day for the brilliant artwork that accompanied his poetry. In fact, one can really think of Blake as being an early manifestation of the graphic novelist. His most famous illustration, “The Great Red Dragon,” was made even more famous by its use in Brett Ratner’s 2002 Red Dragon, the prequel to The Silence of the Lambs. Blake’s “Jerusalem” was written on the heels of the French Revolution and has been performed numerous times as an anti-fascist anthem by musicians such as Billy Bragg. Like Bragg, Blake was intimately involved in revolutionary politics, the energies of which he marshaled toward a bitter indictment of his own England. In “Jerusalem,” Blake offers a harrowing prophetic warning against what he takes to be England’s crass imperialism and brutal industrialization (the “dark satanic mills”), which have endangered the English spirit. His vision is equal parts righteous indignation, divine prophecy, and proto-Marxist politics. It’s not that far from the sort of nightmarish, dystopian vision that one finds in such films as City of Men and 28 Days Later in which a beleaguered human spirit must claw and fight its way against the horrors of tyranny and political oppression.

7. “A Slumber Did My Spirit Seal” (1799) by William Wordsworth

|

A slumber did my spirit seal;

I had no human fears: She seemed a thing that could not feel The touch of earthly years. No motion has she now, no force; She neither hears nor sees; Rolled round in earth’s diurnal course, With rocks, and stones, and trees. |

This short, eight line poem has been traditionally used by young literary critics to sharpen their analytical teeth. In that regard, it serves the same purpose that Hamlet does for budding actors. Wordsworth was a contemporary of Blake and one of the founders of the English Romantic movement. He is often thought of as being the kinder, gentler member of that particular group, which also includes Blake, Percy Shelley, and Samuel Coleridge. Wordsworth is famous for poems that explore the promise of transcendence amid lost innocence, although this poem is altogether different. Written after the heartbreaking death of his young daughter Lucy, “A Slumber Did My Spirit Steal” works, also like Hamlet, as a bitter gravestone epitaph and meditation on death. The “she” of the poem returns to “nature” after her death, but it offers no solace. Nature is instead a cold, indifferent force that renders us helpless as much in life as in death by turning us into mute, powerless apparitions. The entire poem has the eerie feel of a ghost story, as if to say that our dead are well beyond our reach, but they won’t quite leave us. They no longer move with us, but are instead moved as lifeless things and “rolled” by the earth’s indifferent course, along with the equally inanimate rocks, stones, and trees. A similar sense of utter futility and dread operates in such films as Ringu and Ju-on: The Grudge .

6. “The Second Coming” (1910) by William Butler Yeats

|

…Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand. The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi Troubles my sight; somewhere in sands of the desert A shape with lion body and the head of a man, A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun, Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it Reel shadows of indignant desert birds. The darkness drops again; but now I know That twenty centuries of stony sleep Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle, And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born? |

Screenwriters invariably steal from the language of “Second Coming” any time they need a serial killer to sound both cryptic and scary. For instance, Chris Carter stole freely from this poem in writing his largely underrated show Millennium. This shouldn’t be surprising as Yeats, like Blake, was thoroughly steeped in apocalyptic fin-de-siecle prophesy. But he was also involved in the bitter political struggle for Irish independence. Yeats’s “Second Coming” imagines a world seemingly beyond redeeming. Politics have failed to save his Ireland, an aristocratic spirit has failed to lead the masses, and art has failed to inspire humanity, all of which leaves one last option. The loosely biblical “second coming” does not herald peace, love, and understanding, but a cosmic-scale ass kicking. This poem has the same other-worldy, esoteric menace that you’ll find in such films as Stuart Gordon’s Dagon, which also depicts a monster that slithers its way toward a final reckoning with human kind. Modern pundits have taken to using “The Second Coming” to talk about the concept of blowback – the idea that we reap what we sow, and that our current mess in Iraq is the result of historic problems with our foreign relations. That’s a smart way to think about the poem. But I like to think of Yeat’s “rough beast” as part Damian, part Cthulhu, and part Godzilla.

5. “Howl” (1955) by Allan Ginsberg

|

…What sphinx of cement and aluminum

bashed open their skulls and ate up their brains and imagination? Moloch! Solitude! Filth! Ugliness! Ashcans and unobtainable dollars! Children screaming under the stairways! Boys sobbing in armies! Old men weeping in the parks! Moloch! Moloch! Nightmare of Moloch! Moloch the loveless! Mental Moloch! Moloch the heavy judger of men! Moloch the incomprehensible prison! Moloch the crossbone soulless jailhouse and Congress of sorrows! Moloch whose buildings are judgment! Moloch the vast stone of war!… |

Before Ginsberg became the grandfather guru of the 1960s counterculture revolution, he helped define the 1950s beat generation. In the midst of the 1950s culture of conformity and blissful suburban normalcy, Ginsberg offered this brilliant, rambling, blood curdling, prophetic, and brutally honest assessment of the freaks, psychotics, geniuses, poets, and artistic outsiders that operated within the fringes of American culture. Ginsberg is heavily indebted to Blake and presents a harrowing vision in part two of “Howl” in which American culture sacrifices its brightest and most creative minds to the industrial, materialist, soulless demon Molloch. Ginsberg takes the name “Moloch” from Fritz Lang’s film Metropolis, but I think the raw, animal, and sometimes aggressive energy of his poem with its mystic overtones is perhaps better embodied in such films as Wolfen and The Howling. Ginsberg’s poem is something that you don’t read softly and quietly. This poem wants you to listen to your inner beast and defiantly scream the poem aloud to the next full moon.

4. “The Flowers of Evil” (1857) by Charles Baudelaire

|

…If poison, arson, sex, narcotics, knives

have not yet ruined us and stitched their quick, loud patterns on the canvas of our lives, it is because our souls are still too sick. Among the vermin, jackals, panthers, lice, gorillas and tarantulas that suck and snatch and scratch and defecate and fuck in the disorderly circus of our vice, there’s one more ugly and abortive birth. It makes no gestures, never beats its breast, yet it would murder for a moment’s rest, and willingly annihilate the earth. It is BOREDOM. Tears have glued its eyes together. You know it well, my Reader. This obscene beast chain-smokes yawning for the guillotine– It is you, hypocrite reader, my double, my brother! |

Romantic poets drew their energies from divine nature; Victorian poets drew their energies from the refinements of culture; Charles Baudelaire drew his energies from the urban gutter. Baudelaire’s profound influence on literature, art, and modern culture cannot be overstated. Every would-be rebel outsider-artist from Patti Smith to Jim Morrison to hordes of high-school goth kids are in his direct debt. His poems have the attitude of a defunct and reckless aristocrat who’s gone slumming for the night. As the twentieth century approached, Baudelaire argued that culture needed to at long last modernize. Victorian-era culture had produced thoroughly industrialized masses that were, in his assessment, too banal, too bourgeois, and too boring. If art were too matter again and show some real signs of life, then its subject matter needed to free itself from polite society and its language needed to free itself from stifling conventions. The filth, energy, and excitement of the modern world inspired Baudelaire to daringly draw upon the more obscene and infernal aspects of the urban landscapes around him as a new model for poetry. And, in an even more striking gesture, he dares his reader not to enjoy it. The introduction to Baudelaire’s opus, The Flowers of Evil, is called “To the Reader,” and in its conclusion, quoted above, the lurid and voyeuristic detachment that permeates Baudelaire’s work is suddenly and thrillingly cast upon the reader. Reading his work reminds us that poetry need not be the stuff of boring classrooms, but a fearless and shameless art that turns our most obscene vices into the guilty pleasures of spectacle. If you’ve ever caught yourself in your weaker and perhaps more honest moments enjoying such exploitation films as Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust or Russ Meyer’s Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! then you just might have Baudelaire to thank for it.

3. “Daddy” (1963) by Sylvia Plath

|

…If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two–

The vampire who said he was you And drank my blood for a year, Seven years, if you want to know. Daddy, you can lie back now. There’s a stake in your fat black heart And the villagers never liked you. They are dancing and stamping on you. They always knew it was you. Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through. |

Written just before Plath committed suicide, “Daddy” belongs to the confessionalist school of poetry that dominated the 1960s with its interest in self-empowerment, self-expression, and self-liberation. While confessionalist poets sometimes border on so much narcissistic navel-gazing, Plath avoids mere solipsism by welding her fearless introspections with larger cultural myths. “Daddy” derives much its power from the fact that it’s Plath’s personal act of psychic exorcism from her oppressively patriarchal influences, but it’s presented in terms that are as familiar and public as they are horrifying. For instance, in the poem’s conclusion her complex relationship with her tyrannical father and equally problematic husband is rendered in terms of a classic vampire story. Both of them continue to haunt her and hold her in their sway, even after her father has died and after she’s left her husband. Film critics invariably point out that the venerable Count Dracula is traditionally presented as fiendish, aristocratic, overly-sexualized and dripping with masculinity. Vampires, in other words, attract even as they repulse, and Plath knows that these sort of complex, deep-seated psychic apparitions can only be exorcised with an old-fashioned, metaphoric stake through their heart.

2. “Pike” (1958) by Ted Hughes

|

Pike, three inches long, perfect

Pike in all parts, green tigering the gold. Killers from the egg: the malevolent aged grin. They dance on the surface among the flies. Or move, stunned by their own grandeur, Over a bed of emerald, silhouette Of submarine delicacy and horror. A hundred feet long in their world. In ponds, under the heat-struck lily pads- Gloom of their stillness: Logged on last year’s black leaves, watching upwards. Or hung in an amber cavern of weeds… |

Hughes is supposedly the “vampire who said he was you” in Plath’s poem “Daddy.” While it’s risky to extrapolate too much biographical information from works of literature, both Plath’s “Daddy” and Hughes’ own poem “Pike” attest to the fact that Hughes was no stranger to the more infernal aspects of human culture and psychology. After World War Two, British poetry evolved into two distinct camps. Poets such as Philip Larkin developed a stoic and empirically based poetry that attempted to avoid glamour, violence, and other excesses they associated with the spectacle of war. Poets such as Hughes and Plath, too their art in the opposite direction, used poetry to stare down the apocalyptic tendencies in the human condition and confront the roots of our aggression and violence. The pikes in Hughes’ poem are metaphors for the vestigal, brutish impulses found within the depths of British history and the human psychology. The fact that Hughes’ encounters them while fishing in a pond next to a monastery is a reminder that no matter what refinements or religions our culture may produce, there are monsters beneath its surface. What makes this poem so horrifying is that Hughes insistence that such monsters won’t stay submerged. His “Pike” is either a miniature version of Jaws, but with a more subtle and eerie menace, or a singular version of Piranha, but with far less parody and camp.

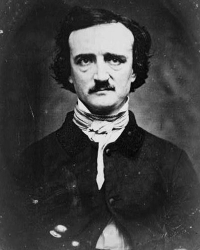

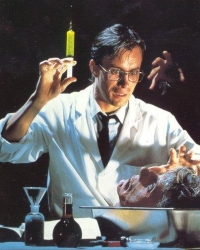

1. “Annabel Lee” (1849) by Edgar Allan Poe

|

…For the moon never beams without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee; And the stars never rise but I feel the bright eyes Of the beautiful Annabel Lee; And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side Of my darling- my darling- my life and my bride, In the sepulchre there by the sea, In her tomb by the sounding sea. |

Poe is arguably one of the most recognizable and widely read American writers, yet, ironically, in his own day he was famous in France and largely ignored by the American public. This is perhaps due to the distaste for the macabre and the creepy in mainstream American culture, but also because the French recognized that beneath the stories of ravens and madmen, Poe’s best work was an avant-garde critique of middle-class, bougeiouse society and an example of the decadent, liberated symboliste literature practiced by such French poets as Baudelaire. Poe’s most interesting work, like that of the French symbolist tradition, is much more than a scary story or simple narrative. The language of “Annabel Lee” is elusive, evocative, and suggests far more than it denotates. The poem seems to provocatively shimmer somewhere between the angelic and the devilish, the sacred and the profane. Poe’s “Raven” was a strong contender for this spot in my countdown, but I think that “Annabel Lee” is more indicative of Poe’s conflicting impulses, which eventually defined the predominate literary aesthetic of his day. The strange mixture of sensuality and morbidity and the fact that the speaker doesn’t let a little thing like death prevent him from enjoying his beloved is reminiscent of Re-Animator and the thousands of Hollywood ghost films that trail behind Poe’s long shadow.

3 Responses to Top Ten Reasons Why Horror Fans Should Be Poetry Fans

Subscribe Without Commenting