Corey and I spent a weekend in NYC at Fangoria’s Weekend of Horror, and I’m still processing all the strange sights and sounds. We were witness to a horror-themed fashion show hosted by the one-and-only Gwar; we met a demented DVD salesman named Twisted Chris; I was nearly impaled by the over-sized spikes on the shoulders of Gwar’s Oderus Urungus; we saw Tom Savini single-handedly destroy the elaborately constructed curtains on the main stage as he made his surprise entrance to be the guest judge of a costume contest.

However, one of the more surprising things about the Fangoria convention was the recurring complaint offered by its guest speakers that the current trend of horror film remakes is bad–REALLY bad– for horror films. For instance, during the Last House on the Left panel discussion, the villains from the original film, (David Hess, Fred Lincoln, and Marc Sheffler) unanimously agreed that the remake of their film is, at best, simply a calculated effort to make money, and, at worst, a film that is helping to prevent real horror films from being made. David Hess explained it like this: what made the original film so subversive and powerful was that Wes Craven and the cast really had nothing to lose. They could take risks without worrying so much about a studio’s bottom line. Fred Lincoln speculated that another thing that made the film so powerful was its intimate and natural connection with the culture and zeitgeist of the 1970s, and so the film loses much of its original tone when transplanted to another decade. The result is that we’re watching a replica of a horror film when we could, if it weren’t for all these pesky remakes, watch real horror films.

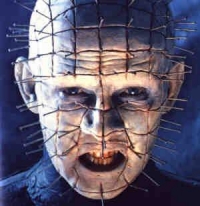

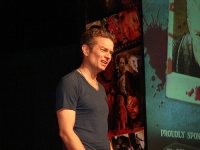

Nearly every panelist or guest speaker said as much over the weekend. Tom Savini hated the Friday the 13th remake. Doug Bradley is appalled by the fact that a Hellraiser remake is being developed, and he cited many of the same reasons offered by Hess and Lincoln— it’s simply a vehicle for making money, it risks nothing, and it crowds the market for new and innovative horror films. Horror fans should instead demand that film makers find ways to keep it gritty and make it shocking. This won’t happen, as one panelist said, if directors insist on using eye-candy from the WB network in their films simply for an increase in revenues. As Bradley put it, we need to avoid warmed-over films and instead “go looking for the new again.”

But perhaps the most articulate explanation as to why we should all be suspicious of remakes came from James Marsters, the Spike-y headed vampire from Buffy. He likened the situation to the difference between New York’s glossy, professional, and strictly for-profit Broadway Theater and Chicago’s non-profit Steppenwolfe Theater. While you’re guaranteed to see a good and entertaining show on Broadway, you’re not likely to encounter the sort of gutsy, unpredictable, and challenging theatrical experience offered by Steppenwolfe. A non-profit theater company can take risks with their material, artistry, and audience expectations in a way that other theater companies can’t because they have to be concerned with simply filling their seats every night. By the same logic, remakes will always be problematic because they’re more likely to simply be commercial ventures, and they seldom take the same risks as the original.

On the one hand, I am completely sympathetic with all of these arguments. While I actually liked the Friday remake, I admit that it didn’t have the same impact, or creepiness, or gut-wrenching fun as the original films. And I cannot fathom why anyone would think it’s a good idea to do a remake of Hitchcock’s Psycho, a damn near perfect film, other than it might be a convenient way to make a buck. Still, I can’t help but think that for every big-budget, glossy remake, there are dozens upon dozens of horror films being made that have no mercenary intentions, or any intentions at all other than to scare the bejeesus out of you, or provide an altogether new twist on an old story. 2008’s Dawn of the Dead is a perfect example of a director making a classic film seem new again. And if it weren’t for remakes, we wouldn’t have such modern gems as The Fly, The Thing, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, or the many good versions of Dracula. Good or bad, there have always been remakes, and, as the good book says, there’s really nothing new under the sun. Both Hellraiser and Last House on the Left were, technically, remakes of earlier literary works. I think much of what was said at Fangoria stems from what must be the uncomfortable experience of watching your original work turn into a simulation of itself, much like walking into a wax museum and seeing your life-sized replica. Still, the panelists at New York’s Fangoria offered an interesting challenge to horror fans and film makers alike — without at least some risk, there’s no possibility for genuine horror.

6 Responses to Where Have all the Real Horror Films Gone?

Subscribe Without Commenting