“Draw to one point, and to one centre bring Beast, man, or angel, servant, lord, or king.” –Alexander Pope, from “An Essay on Man” |

“It’s like death on a cracker!" –Choptop, from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 |

“The death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetic subject in the world" –Edgar Allan Poe, from “Essays on Composition” |

When Edgar Allan Poe famously declared that nothing is more poetic than the death of a beautiful woman, he did not simply mean that poetry is voyeuristic or an act of sublime spectacle. He intended his statement to be a corrective on the crabbed, stuffy poetry being produced by the likes of such neo-classical poets as Alexander Pope. In particular, Poe disagreed with Pope’s argument that poetry should reflect the virtues of a “Golden Age” populated by iconic shepherds. In his “Essay on Criticism,” Pope explained that poets are “not to describe shepherds as shepherds at this day really are, but as they may be conceived then to have been when the best of men followed the employment.” He envisioned a utopian garden in which poetry could unite man and best, angel and devil. Lute-playing Shepherds in gardens of perpetual spring who sing and pitch woo in perfectly measured dactylic hexameter may be the stuff Poetry (that’s with a capital P), but not, Poe would later insist, the stuff of real poetry—an art form that strips language and meaning down to its unaccommodated and fundamental nature. For Poe, this fundamental nature is, to put it eloquently, the death of a beautiful woman; or more bluntly, it is sex and death. Poe helped orient poetry away from the pretentious fictions of a golden age and instead toward the truer, albeit darker heart of the human condition. He called for an art without pretense, an art that would not shy away from voyeurism, exploitation, spectacle, and the twin principles of attraction and repulsion that have been the foundation for all of our glorious as well as inglorious history. Sex and death, love and war. Poetry lays bare our most human of impulses.

Fifty years later, at the turn of the century, Thomas Edison would offer the same corrective for the newly invented medium of film. The first exhibited films on record, all from the late 19th century, were little more than curious parlor tricks that would adorn store-front windows or serve as two-minute intermissions during vaudeville acts. They were patently genteel, tame, and boring. The 1888 film entitled Roundhay Garden Scene by Luis le Prince is credited as being the first actual “film” and features, as one might imagine, a garden scene in which the actors (if one can call them that) briefly walk across a richly decorated yard and laugh. Likewise, the films of the famous Lumiere brothers from the same period typically feature gardens, fountains and other scenes of bourgeoisie bliss. When not inventing light bulbs, Edison was the consummate salesman who understood that spectacle, as much as ingenuity, fuels the American economy. His first films, some of the earliest in America, gave consumers what they really wanted: sex and death. Consider the first titles he produced: Muscle Dancer (1894), Ella Lola, Turkish Dancer (1898) The Electrocution of an Elephant (1903), and Frankenstein (1910, directed by J. Searle Dawley). With his emphasis on voyeurism and spectacle, as well as other forms of visual attraction and repulsion, Edison helped transform film from a polite and gimmicky storefront distraction into a nascent form of American cinema that would eventually evolve into the modern day horror film, particularly those that appeal to the more primitive impulses of the spectacle. The history of American cinema is, in other words, a history of the slasher film.

For instance, consider the particularly strange, but ultimately canny, logic behind the sequence of his first films. Edison’s first two films (Muscle Dancer and Ella Lola, Turkish Dancer) are pure exploitation. Both are under one minute in length, but feature enough gyrating flesh to satisfy even the most insatiable voyeur.

Edison, I would argue, understood the innately exotic appeal of the moving picture. Not content to film pretty, but static English-style gardens, Edison instead offers an aesthetic that visually moves both its subject and its audience. And part of the appeal of Edison’s first films, aside from the gratuitous flesh, is precisely this invitation to shamelessly gape at what is at once familiar to us (the human body) as well as strange (belly-dancing and body-building were still exotic occurrences at the turn of the century). In other words, both of Edison’s first films mix the eroticism of old-fashioned sex appeal with a sense of the unfamiliar. Both the Muscle Dancer and Ella Lola are seductive, but also strange enough to be unsettling.

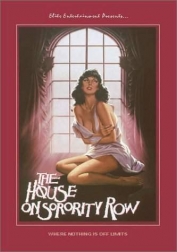

The same kind of binary impulse is at work (albeit more aggressively) in classic slasher films, as evident in the images below.

The first image (a poster for the 1983 film The House on Sorority Row) features a depiction of Kate McNeil in a pose that is both seductive and menacing. She is on display as both odalisque and sacrificial object. The second image (a poster for the 1987 Sorority House Massacre) depicts a voyeuristic killer (a staple of the slasher genre). The killer watches his victim as she undresses. We watch them both. As their posters suggest, both of these films invite us to gape, even if doing so is as ultimately deplorable as it is pleasurable. We are invited to share in the slasher’s guilty and unsettling act of voyeurism, becoming both his victim and his accomplice. This is the logic of the spectacle. They attract and satisfy even as they horrify us. For instance, film critics have routinely called attention to the fact that slasher villains—from Michael Myers to Freddy Krueger—often play the dual role of psychokiller and moral avenger. They kill off the least likable and most morally corrupt characters first and spare the virtuous “final girl,” who in turn defeats the slasher This is an ambivalence that moves the audience in several directions at once. And taken together, the images above underscore this mixture of attraction and repulsion that defines both the slasher and Edison’s early aesthetic of the spectacle.

Edison’s 1903, The Death of an Elephant, marks an advance in the early development of this aesthetic.

This disturbing film depicts the real-life execution of Topsy, a Coney Island elephant that turned dangerously, violently rogue. Edison filmed the event as an attempt to discredit Westinghouse and Tesla, his rivals in the commercial development of electricity. As a marketing ploy, Westinghouse and Tesla suggested the use of their patented Alternating Current system of electricity as a humane and practical mode for executing the elephant. Edison decided to film the event as an attempt to market his own Direct Current by dramatizing the dangers of AC. Edison’s film failed as advertising propaganda and AC became the standard. However, once released, The Electrocution of an Elephant became a sensation and helped popularize the still-new medium of film while generating considerable profit for the struggling Edison Manufacturing Company. The spectacle of the electrocution, it turns out, was actually good for both business and film.

Of course, the fact that such a film could generate so much revenue is startling, and perhaps shameful, even if it documents what was intended to be a humane solution to an unfortunate problem. But it also points to several incontrovertible facts: 1) people love spectacle and will pay to see it; 2) cinema, as Edison proved, is a natural medium for spectacle; and 3) we are fooling ourselves if we think that we, or the art of film, can (or perhaps even should) be beyond this. Sex and death, dance and disease – these are innately human impulses.

Edison’s recently recovered 1910 version of Frankenstein, which he used to revitalize his newly established film studio, is both an important monument in cinematic history, as well as a near-perfect synthesis of the impulses of attraction-repulsion that Edison sought to develop in the spectacles of his early films.

Of course, Whale’s 1931 Frankenstein established the iconic version of the monster with its bulging neck bolts and big shoes. But Edison’s version is not only truer to Mary Shelley’s concept of the creature, but also contains some of the roots for the horror genre’s more exploitative and subversive offspring. For instance, Whale’s version establishes the conventional fire-and-pitchfork ending of the classic monster movie. The creature is a fiend, an inhuman abomination who must be destroyed and who warrants only the thinnest amount of sympathy or attraction. Edison’s version, on the other hand, features a surprise ending in which it is implied that Victor Frankenstein and his creature are actually one and the same, or at least mirror images of each other. At the conclusion of Edison’s film, the creature gapes at its image in a mirror before vanishing, leaving only the mirror images. Victor enters the room and sees the creature’s after-image in the mirror before it transforms into his own. The implication is that when Victor (and by extension the audience) gapes in horror at the creature, he also gapes at his own monstrosity. Roger Ebert has pointed out that the influence of the slasher film has led to an increased use of a subjective point-of-view that encourages audiences to identify, albeit uncomfortably, with the slasher. But the influence originates further back in film history. Unlike Whale’s Frankenstein, Edison’s 1910 version is not a monster movie. It belongs, along with the slasher films that would arrive more than half a century later, in the darker, older heart of cinema where monsters are our kindred spirits.

Edison is exploiting the newly fashionable field of Freudian psychoanalysis with its emphasis on the dual nature of the human mind in order to make a buck, but he’s also establishing the foundations for American cinema. An emphasis on this sort of crude dual psychology has been the feature of American films from Birth of a Nation to Beetlejuice. Born out of an ingenious capitalist’s penchant for spectacle, American cinema has always derived its appeal from an unapologetic exploration of the seemly and the unseemly, the attractive and the uncanny. That this binary of attraction and repulsion finds its perfection in the iconic struggle between the knife-wielding killer and the nubile college co-ed is therefore hardly surprising. But it still irks film critics such as James Berardinelli, who insists that the cheap exploitation of From Dusk ‘Til Dawn might be “great fun, but not great art.” His assumption is that real art can’t involve such cheap thrills and chills. Poe would say otherwise. The history of American film suggests otherwise as well. American film does not hark back to a lost Golden Age, nor does it unite man and beast, as Pope would undoubtedly have it. Poe insisted that poetry is the raw stuff of love and hate, lust and loathing. These are the same impulses that get us into theater seats. Art doesn’t necessarily make us angels. Edison knew this dirty little secret, too. At its roots, American film is slasher film.

Subscribe Without Commenting