Horror has always been a vehicle for social commentary. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a metaphor for how our prejudices and moral failures create our own monsters in our own image. Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a famous metaphor for cold war hysteria. Still, not every horror film is up to the task of serious social commentary, no matter how hard it tries. Here are a few examples of horror films as social commentary that work, as well as a few that don’t.

1. Alien incarceration is a good metaphor for the evils of racism.

(District 9, 2009)

I still can’t get over how good this movie is. It’s a textbook example of how to properly make the most out of faux-documentary storytelling and filmmaking. The film was adapted from a 2005 short film called Alive in Joburg, and inspired by events that took place in District 6 in Cape Town during South Africa’s apartheid era. The film movingly explores the effects of xenophobia and forced segregation as one of the chief bureaucrats who oversees District 9 is forced to live as a hunted and despised alien. In doing so, not only does he learn to have compassion for those who have been so unfairly oppressed, but regains his own humanity, even as he transforms into an alien himself. At the same time, we learn to sympathize with the alien Christopher Johnson and his young son, both of whom simply want to go home. They’re far more decent and sympathetic than those who oppress them. Honestly, I haven’t been that emotionally invested in a film in years. It’s a deeply moving and thoughtful metaphor for just how much we lose ourselves when we hate those who are different from us.

2. An alien invasion is not a good metaphor for Mexican immigration.

(Monsters, 2010)

Monsters wants to be District 9. But I have seen District 9. I love District 9. And Monsters, you are no District 9. If you pretend that Monsters is just a monster movie with no other agenda, then it works fine. The effects are good (but sparse), the story is good, and it involves likeable and interesting characters who have to sneak past a quarantine zone where Earthlings have just had their butts kicked by giant, squid-like monsters. The quarantine zone happens to be Mexico, and the protagonists are desperate to sneak into the U.S. by any means necessary. Their plight warrants a lot of sympathy and has obvious analogies with immigration along the US-Mexican border. Had the film stopped here, I would have been fine with it, but this is where it gets confusing. We’re meant, I think, to agree with the protagonists who begin to realize that the aliens are misunderstood, and are actually beautiful — if you find giant, slithering, crevice-probing tentacles to be beautiful. Call me old-fashioned, but I think they’re horrifying. And these aliens also have the habit of leaving their eggs stuck to the sides of every tree in every forest they slither through. The overall message is that we should be peaceable and ecologically friendly, and just live and let live when it comes to tolerating the interplanetary aliens among us. I’m as liberal as they come, and a literal card carrying member of both the ACLU and the Sierra Club. I believe in saving the planet, preserving the environment, and keeping our borders open for fair and legal immigration. But I wanted the US military to nuke those squishy, disgusting aliens back to whatever planet they came from. As a monster film, this was very good. As a metaphor for how we should rethink our immigration policies, using the aliens in this film was just plain crazy.

3. Zombies are a good metaphor for mindless consumerism.

(Dawn of the Dead, 1978)

Zombies have always tapped into the fear that we’re all little more than flesh and bone with nothing more noble or spiritual to animate us or guide our behavior. Zombies are terrifying because, as Barbara puts it the 1990 remake of Night of the Living Dead, “we are them and they are us.” This idea reached its apex in George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, in which mindless, suburban consumerism is explored through the vehicle of a zombie infested shopping mall. I was a teenager in the 80s, so mall culture is a part of my DNA, but after watching this film, I do feel a little guilty whenever I mindlessly wander around one with an Orange Julius in hand.

4. Zombies are not a good metaphor for new media/blogging.

(Diary of the Dead, 2007)

Romero once said that whenever he sees a social problem, he sticks a zombie to it in order to explore it. But it doesn’t always work. I actually agree with the premise of Diary of the Dead. I love the ephemeral pleasures of YouTube as much as the next guy, and I think blogging is a great form of community-building and political empowerment. But blogging is no substitute for professional journalism, and thinking that it is could make us ill-informed, intellectually lazy, and socially disconnected. That’s a great theme that great writers such as Noam Chomsky and Neil Postman explore in-depth in their numerous books and essays. Sadly, this theme doesn’t make for a great zombie movie. Throughout this awful, unwatchable mess of a film, we’re supposed to want the characters to stop filming and do something to save their fellow human beings. We’re supposed to want them to be more connected to reality instead of their private, mediated version of it. Instead, I wanted to scream at Romero to connect with his audience by making a real zombie movie.

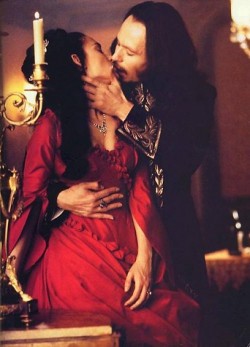

5 .Vampirism is a good metaphor for venereal disease.

(Bram Stoker’s Dracula, 1992)

Bram Stoker suffered from syphilis when he wrote the book that forever established the vampire as an icon of horror. His version of the vampire is sexy, seductive, and diseased. Vampires had long been repulsive and fearsome, but Stoker made them equally attractive, and I think it’s this capacity of eliciting both of those powerful emotions at once that makes the modern vampire so captivating. Francis Coppola’s rendition of Stoker’s novel makes this clear, as his Dracula is both a demonic fiend and also a debonair but diseased man of civilization (or “syphilization,” as Van Helsing puns). Coppola pushes that metaphor about as far as he can by linking vampirism with the stigma of HIV, but it works. Near Dark is another example of how well this metaphor works in exploring the ravages and allure of disease. Behind their fangs, the vampires in Near Dark are really sex-crazed, drug addicts in desperate need of medical treatment, if only they would stop partying long enough to take that first step and admit they have a problem.

6. Vampirism is not a good metaphor for the moodiness of teenage love.

(Twilight, 2008)

Romeo and Juliet, The Breakfast Club and Freaks and Geeks are notable exceptions to the general rule that teenage drama is boring and trivial. There’s a fancy neurological term for why things seem so disproportionally melodramatic when you’re a teenager. It has something to do with the still developing neural pathways of the teenage brain. Of course, there have been some notable adolescent vampires – Homer in Near Dark and Eli from Let the Right One In are obvious examples. But those characters work because they’re adults stuck in a child’s body. They have real problems. The vampires in Twilight are perpetual adolescents with high school problems. Being stuck in that stage of emotional and intellectual retardation is, I suppose, horrifying. But vampirism is not a good metaphor for moody teenagers because NOTHING is a good metaphor for moody teenagers. Also, vampires don’t hang out in trees. Or play baseball. Or sparkle.

5 Responses to Horror Makes for Good Social Commentary – Except When it Doesn’t

Subscribe Without Commenting