corey’s review…

code black entertainment was kind enough to invite evilontwolegs to a screening of (and additionally supply dvd copies of) the recently released slasher somebody help me. reviews of the low-budget thriller have ranged from oddly fervid (slasherpool) to aggressively hateful (the vault of horror). part for the reason for such varied opinions is that while this is billed as a slasher film, i’m not sure the traditional slasher film audience is who it was intended for. director chris stokes is better known for you got served and his entry into the house party franchise, and this film targets the same general audience as his previous efforts, which is not typical horror aficionados. i saw this film at a screening held by a local hip-hop station and the audience really seemed to respond to the film which left me feeling that while this film may not be my cup of tea, that may just be because it wasn’t really intended to be. however, this blog is intended for horror connoisseurs and regardless of precise target demographics, somebody help me is a slasher film. thus is through the rather critical prism of slasher film history that i’ll be watching and judging it.

somebody help me opens with a flashback to 3 years ago where we see several girls in dog kennels crying as their tormentor stomps around menacingly. at least i think that’s what was going on since the scene is really just a grainy mixture of blacks and greys which luckily quickly gives way to a long kubrick-ian helicopter shot of the forest laid behind the opening credits. imagine the helicopter shot leading to the hotel from the shining… only add in a bunch of annoying flash frames, mtv hip-hoppy film speed changes and bad music.

as the credits draw to a close we’re introduced to our main characters, 2 young couples heading into the woods for a weekend birthday party. they seem a little anxious about leaving the city, but seem to settle in nicely once they arrive at “uncle charlie’s” cabin.

the two male characters head into town to pick up party supplies, where they meet sheriff bob. the sheriff seems to be giving them a hard time until he asks where they’re staying. “my uncle charles bronson’s cabin, sir.” wtf? i spent the next hour and a half of the movie waiting for this… unfortunately the uncle never makes an appearance. perhaps they’re saving that for somebody help me too?

stocked up with chips and beer, the party planners head back to the bronson estate. in addition to the two original couples, the party has grown to include three white couples. with the aid of balloons and nausea-inducing pop music, our ten party goers proceed to execute the lamest birthday party ever attended by people over the age of eleven.

as the party is winding down, two of our newly introduced couples decide to wander off into the woods with no blankets to have sex. the rest of the party heads to bed, where charles bronson’s nephew subsequently is terrified by a nightmare about a little girl on a swing set.

the next morning the six non-forest wanderers wake to find the two couples that slipped off into the woods never returned. they discuss calling the police, but doing that would end in the uncle being notified and they’d rather that not happen. instead they decide to search the woods aimlessly, and it seems that daylight lasts less than an hour in these mountains as they quickly need to resort to using flashlights in their search despite having started as soon as they woke.

the remaining white guy says that they should split up to cover more ground and to call each other if they find anything. since you can’t make a horror movie anymore without removing cell phones from the equation, he’s promptly informed “you know we ain’t got no service up in these woods!” still, split up they do and almost immediately the last white couple vanishes.

the two remaining couples discuss whether to call the police again and eventually decide to do so. throughout all of this the film has been peppering in a few jump scares, all of which are pretty much derivations of the following. music builds, music builds, music builds, music climaxes as we see the killer walk by in the background of the shot. this staple of horror films happens again and again in the film, but there’s something a bit off about it. below is an example…

the killer walks from screen right to screen left just as the music hit occurs. this is fine… but what is the killer doing? normally in this type of shot he’d be stalking the victim we see in the foreground or something to that effect… in most of these shots he just seems to be on his way somewhere like he’d just jumped up to grab a soda from the fridge and was heading back to the sofa.

anyway, now that sheriff bob has been notified, we occasionally cut to see what our killer is up to. it seems he’s locked all the missing kids in dog kennels…

and has begun torturing them, a la hostel.

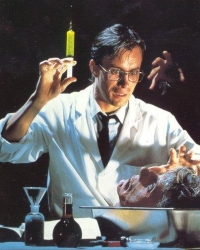

the movie follows a definite ‘whodunnit’ structure, systematically pointing fingers at the town kook, the sheriff, the deputy and anyone else who happens to wander in front of the camera. when stalking, the killer is shown wearing a clear plastic mask that hides his identity. the problem with all this is that right from the beginning we’re shown torture scenes where the killer is clearly visible with only a surgical mask covering his mouth. the only conclusion i can draw from this is that these torture scenes were added after-the-fact, much in the same way captivity had all the gratuitous violence added after bombing overseas. i rarely use this term, but the violence here is gratuitous, serving no purpose and even detracting from the story. as the plot unfolds we learn the killer is a plastic surgeon gone bonkers who likes to perform a little unnecessary cosmetic surgery on unwilling victims from time to time. how exactly does scalping, removing fingernails, plucking out eyes or ripping out teeth fit into this? in one case the killer removes someone’s ear which seems in keeping with his specialty… but in every other case it seems it’d have been better to make the villain an evil dentist, psychotic hair stylist, depraved optometrist or deranged manicurist.

in predictable fashion, the police don’t really believe what our four heroes have to say. back at the station, sheriff bob is trying to decide when to start muttering “damn punk kids” to himself when his deputy comes up with something. “hey, sheriff… you don’t think this has anything to do with those other college kids that went missing exactly three years ago tonight?” sheriff bob’s reply? “deputy, how many times do i have to tell you… you mention that again, i’ll have you badge.”

wait, what? lose your job for mentioning highly relevant information in a respectful and courteous tone?

by this time the two remaining boys have let their girlfriends get abducted when they decided to go do some hardy boys sleuthin’ and left the girls back at the house. the two boys decide to do the only reasonable thing… since they’ve had no luck finding their friends or significant others and the police aren’t helping as much as they’d like, they decide to pack up all of their belongings and drive several hours back to “the city” to get help.

but wouldn’t you know it… “that sonofabitch cut the wires.” with no usable mode of transportation due to untimely wire cutting, they decide to walk to the police station. on the way there, a white guy stops and asks if they’d like a ride. a white guy in rural america stopping in the middle of the night to offer two black guys carrying a baseball bat a ride? you just know this guy is trouble. well, since the boys haven’t seen the torture scenes, they don’t realize this is the killer and so they hop in the car. the good samaritan tells them that he’ll take them to his place instead of the police station because the sheriff is already there checking something out. they completely buy this and wait patiently on the couch while the killer “goes to get the sheriff” who he says must be in the john.

next comes the movie’s most ridiculous moment, and that’s saying something. one of the boys goes to use the phone but it shoots a bit of cgi smoke in his face and he begins to get all wobbly as though he were about to say “goodness gracious, i think i’ve got the vapors” (see below). i’d like to think that the killer has his whole house rigged this way and frequently knocks himself out cold by accident reaching for a pepsi in the fridge or trying to switch his tv from dvd to xbox.

now all alone, charles bronson’s nephew runs into the little blond girl from his dream who helps him avoid capture and says she’ll help rescue his friends. several times during all of this our heroes stab or bludgeon the killer who, of course, appears dead. each and every time they do this they drop their weapons and turn their back on the killer. i understand this has been a staple of this type of film since halloween… but no one’s really used it more than once in a non-ironic fashion since the 1980s.

after one of these “oh, we killed him so now we’re safe” moments, the little girl leads our hero to the dog kennels to rescue those of his friends still alive. this is my favorite moment in the movie as our hero does the unimaginable and “forgets the keys.” the music swells as one of the caged girls screams “oh hell no, you did not..” and continues to build as the little girl pauses dramatically before she reveals where the keys are. “they’re in his pocket.” the music crescendos in a ludicrous fashion as the caged girl begins screaming, “WHOSE POCKET? WHOSE POCKET!?!”

i’m sure you can predict what happens next. they get the keys and then there’s a few more instances of hitting, stabbing or tripping the killer and everyone erroneously assuming he’s dead. before the whole thing draws to a close there’s a lot more over-the-top music cues, heavy-handed editing and idiotic behavior like people screaming up the stairs at the top of their lungs that everyone needs to be quiet because the killer might hear them. at the end our two black couples have survived largely unscathed and the killer has been shot dead. OR SO THEY ASSUMED. we’re left with the deputy informing our heroes that they only found a blood trail, but that it’ll be ok because (and i quote) “we put out a full investigation. he’s not getting away.” just as the credits are about to roll, we see the killer (in a new set of clothes and not obviously bleeding, bruised or, as one might assume, dead) and the little girl in a car slipping past the “full investigation” (aka, road block), and getting away.

so ends somebody help me, leaving a lot of room for a sequel and a lot of confusion in its wake. here are a few of my thoughts…

it’s been formulaic for decades to kill the token black guy first in the horror genre, so perhaps this film is attempting to make a statement by turning that on its head. within the film, only white characters are killed or tortured and at the end it appears that of our 10 party-goers, only the black characters have survived. however, if you watch closely at least one of the white characters was still alive in the cages, but he is conspicuously missing from the group of huddled survivors in the film’s final moments (i’ve read that you can see this missing character being wheeled out on gurney in a deleted scene, but that only makes his exclusion from the final cut odder). lines like “that’s white people for ya” following that same character’s decision to split up during their earlier search make the intent of all this seems unlikely to be a study of racial relations in the slasher genre. even if it is, then it’s sloppily executed and completely ineffective.

this is a flawed film from beginning to end, but the film’s biggest and least forgivable flaw is that it simply has no heart… you get no sense that there was any joy involved in its crafting. usually with films of this type you can tell that the filmmakers truly have affection for the genre and had fun making it, regardless of the quality of the final product. that is not the case here. i get the feeling the only reason this was a slasher film is because that’s the only genre the director could get enough money together to make and he’d have been much happier using this same cast to make something a little closer to his heart. it’s obvious stokes has seen films from the genre as he steals from them unabashedly, but it feels as though he took a weekend crash course in slasher films and didn’t realize that a lot of the elements he was borrowing became cliché and ineffective long ago. repeating the “stab the killer, drop your knife, only to have the killer rise again” gag no less than four times with little to no changes is inexcusable. blanketing every scene in slowly building suspense music that attempts to startle the audience every time a curtain flutters or a tree branch snaps quickly becomes dull and desensitizing.

ultimately the film just collapses under its own weight, illogically combining classic slasher conventions with confusingly supernatural elements. it’s unclear where this little girl came from or how she entered our character’s dreams… just as you begin to assume she’s a ghost, the film seems to say that she’s perfectly tangible and never resolves this issue. the killer is a plastic surgeon gone mad, but follows few of the behaviors that would seem to dictate and instead seems to just run around changing clothes every few minutes, driving his car aimlessly, torturing people for no rational (or even psychotically irrational) reason and rigging his appliances as aerosol poison dispensers. if the intent was to serve as an introduction to slasher films for an audience that may have never ventured into that genre otherwise, the filmmakers may well have succeeded in their goal. but for horror fans, this is just another boring hour and a half that attempts to cash in on the creativity of other films while offering nothing new itself.

if you wish to judge for yourself, you can purchase the dvd or see the trailer at code black entertainment’s product page for the film.

Jon’s Review…

Somebody Help Me features R&B performers Marques Houston and Omarian Grandberry and is written and directed by their music producer and burgeoning entertainment mogul Christopher B. Stokes, whose film credits also include You Got Served and House Party 4: Down to the Last Minute. Somebody Help Me is largely a vehicle for the very popular and talented Houston and Grandberry, and I’m sure that their large numbers of fans will guarantee at least some success for this film, even though the script consists almost entirely of broadly sketched horror film clichés: a remote cabin in the woods, a clash between urban and rural cultures, a demented killer who’s also a tightly kept local secret, and an annoying but benevolent ghost-like child. Ultimately, none of this works and the film sputters to a nearly incomprehensible conclusion.

To be fair, there are a few interesting touches in this film, such as the fact that it initially bends over backwards to deflect stereotypes. I was expecting the local sheriff of the town where Houston and Grandberry are partying with their friends to be yet another rustic hillbilly. However, for the first part of the film Sheriff Bob seems professional and actually concerned for the young people vacationing in his town. Grandberry, especially, seems intent on resisting stereotyping by being deliberately polite at every turn, even when he feels that Sheriff Bob is doing nothing to find his missing friends. It’s as if he’s trying to say that he may be urban, and things might be turning violent around him, but he’s not going to play the role of thug. He’s always a gentleman. And I like his character very much. It’s all the more disappointing when the film then proceeds to indulge in one cliché after another.

Some of these clichés were so problematic that they derail the film and make it difficult to watch, especially the bits that borrow too heavily from recent shock films such as Hostel and Wolf Creek. I was not insulted by the scenes of torture and brutality in either of those films. They were difficult to watch, but also complex and a necessary part of the films. The torture scenes in Somebody Help Me, all of which were conducted by a baffling plastic surgeon turned killer, weren’t nearly as gruesome or as fearlessly realistic as either Hostel or Wolf Creek, but the sheer arbitrariness of them were exploitative in the worst kind of way. They weren’t necessarily excessive or voyeuristic, but were pointless and included only because other recent horror successes have featured such scenes. In truth, this was the first time I’ve ever been insulted by horror film violence.

It’s not that I can’t forgive a cliché or two. I can even enjoy clichés when they’re part of a well-made and otherwise well-written film. For instance, 28 Days Later is yet another apocalyptic zombie film with a dash of anti-establishment rhetoric. I’ve seen that premise dozens of times, and yet 28 Days Later manages to pull it off due to the sheer force of the director’s sincerity and skill. It’s not just the clichés in Somebody Help Me that make it a mess of a film by the its conclusion. Nor is it a matter of bad acting, as Houston and Grandberry are often charming and believable, despite the film. And Stokes is a capable enough director, but I suspect that he simply does not care enough about this material, and the result is a technically mediocre film with too many gratuitous sequences and a final lack of sincerity. For instance, the showdown between Houston and the killer loses whatever meager vitality the script might have lent it because it is simply too long, too drawn out, and much of it feels like filler. “Somebody Help Me Find My Keys” may have been a better fitting title as the film borders on parody at one point when Houston must once again battle the killer at length because he can’t find the keys to cages where his friends are being kept. Also, throughout the film, Houston inexplicably refers to his uncle “Charles Bronson.” He and the sheriff even have a long conversation about what a great guy Charles Bronson is. I have to believe that this was an intentional attempt at humor of some sort. The entire film would have been saved for me if a pistol-toting Charles Bronson lookalike would have made a surprise appearance as Houston’s uncle. But, alas, there were no such gems to be found. This film begs to go in the direction of parody, and I wish Stokes would have let it, but he insists on trudging the film forward to what he assumes a horror film should be. It’s a dry, boring endeavor, and based on the strangely humorless gag-reel that accompanies the DVD of Somebody Help Me, nobody on the set ever had fun making this film. I don’t doubt the talent of everyone involved in this project, and they might make a quick buck or two from it, but as a fan of horror films, I hope they never try it again.